Deferred School Maintenance: Pay Now or Pay More Later

Deferred maintenance in K-12 schools has become a $271 billion problem, according to the 2016 State of our Schools: America’s K-12 Facilities report released by the Center for Green Schools at the U.S. Green Building Council, the 21st Century School Fund and the National Council on School Facilities. Adding lifecycle costs brings the estimate up to $542 billion. The report focuses on 20 years of school facility investments nationwide and the funding needed to make up for annual investment shortfalls in essential repairs and upgrades. Only three states’ average spending levels meet or exceed the standards for investment: Texas, Florida and Georgia.

Deferred maintenance in K-12 schools has become a $271 billion problem, according to the 2016 State of our Schools: America’s K-12 Facilities report released by the Center for Green Schools at the U.S. Green Building Council, the 21st Century School Fund and the National Council on School Facilities. Adding lifecycle costs brings the estimate up to $542 billion. The report focuses on 20 years of school facility investments nationwide and the funding needed to make up for annual investment shortfalls in essential repairs and upgrades. Only three states’ average spending levels meet or exceed the standards for investment: Texas, Florida and Georgia.

New schools are exciting and beautiful, but the initial cost of construction accounts for only 10 percent of the facility’s lifetime cost. The remaining 90 percent must be funded so the building can serve students and educators as intended. Many districts struggle to fund ongoing facility maintenance. The State of our Schools report recommends adding at least $19 billion annually to the existing average of $42 billion appropriated to address deferred maintenance annually.

Most districts spend an average of 10 percent of their general operating funds for annual maintenance and operations each year. Most general operating funds are not budgeted to handle major repairs for components such as roofs and HVAC systems.

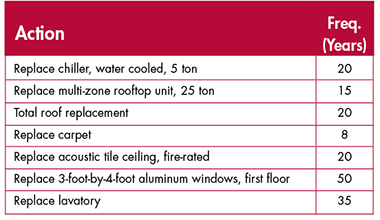

Typically, school buildings deteriorate at a rate of approximately 2 percent per year. If 2 percent of a facility’s total value is set aside each year, those funds can pay to replace facility components as they reach their end-of-life cycles. A building’s lifecycle might be 50 years, but individual components including roofs usually only last 20 years.

Inevitably, most school districts encounter monetary shortages at some point, and non-human assets usually bear the brunt of funding cuts. After all, roofs and boilers can’t petition their cases at board meetings when their budgetary needs aren’t met or make their voices heard during contract negotiations.

In the short term, moving a portion of maintenance funding to other operating funds may seem like an attractive option to get through hard times, but some districts make a habit of it. For example, some districts have moved upwards of 30 percent of their capital fund to operating funds, causing deferred maintenance needs to increase dramatically.

Many school systems dig out from large deferred-maintenance backlogs by combining one-time bond issues. Other districts implement permanent improvement levies where funds are used only for deferred maintenance and cannot be transferred to operating accounts. Permanent improvement levies enable districts to budget for big-ticket items when they are due for replacement, such as roofing and HVAC systems, and avoid compounded deferred maintenance costs. The biggest challenge is convincing taxpayers that a deferred cost is a compounded cost. If a district doesn’t set aside monies for roof repair and replacement beyond its useful life, the cost will compound due to water damage, mold permeation, etc.

Districts can save money if they include deferred maintenance costs in a facilities master plan. They decide what buildings should be kept “as is,” renovated, replaced, rebuilt or closed based on student demographic trends, total budget constraints, the district’s educational vision and the funds needed to support that vision.

When deferred maintenance issues are considered in isolation, the political will to address them wanes when compared to new construction and personnel investments. Packaging deferred maintenance within a broad facilities master plan provides an opportunity to closely link behind-the-scenes investments with high-profile matters of construction needs and educational vision. In the case of a broader capital campaign, districts have the opportunity make a compelling argument that funding for new construction must include funding to properly maintain facilities for the long haul.

Scott Leopold is a project director and GIS analyst for DeJONG-RICHTER. Since 2005 he has provided school districts with the technology tools they need for successful planning.